Featured Object

Featured Object. Linen was used for towels and other types of domestic textiles in the Ottoman Empire. Flax was grown near rivers in western Anatolia and in the Pontus, and spun into thread in those places as well as in Egypt. Records also show that city-dwellers grew small amounts of flax, judging by combs, and bundles and seeds of flax found in inventory lists for the garden suburb of Üsküdar, on the Asian side of the Bosporus. The towel is in a tabby structure, according to colleagues at the Cleveland Museum. Weavers inserted a relatively thicker weft in bands up and down its length, perhaps to create a fabric that would absorb better. They left the spaces at each end empty, though, in order that they could be decorated with colourful embroidered motifs--in this case pots of flowers. The embroiderers used silk, but also a metal tinsel or lamella, which they pushed between the threads and then flattened into shape. Its relatively small size suggests it might have been a hand towel, but is does not show many signs of wear.

All information about the object from the Cleveland Museum of Art, inventory no. 1956.683

Linen, tabby-weave; silk and metal embroidery. Ottoman Empire, probably nineteenth century, 129 x 49.9 cm.

Interested in terrycloth, technology, and towels? Stream a talk on the topic, via the Textile Museum's Vimeo Channel.

Featured Object. An enchanted forest...this piece of fabric was probably part of a garment, maybe a tunic. Several pieces of it are in collections in North American museums -- this one is at the Metropolitan in New York. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts has a piece that was possibly part of the same article of clothing. The piece in New York is partially stained, which may indicate that it was found in one of the medieval garbage dumps of Egypt. It was probably picked up by a person rummaging through the heaps, sold on, and was eventually purchased by well known dealer Dikran Kelekian (d. 1951). Scholars attribute it to Syria, c. 1200s. Exotic birds, griffins, and fox-like creatures are suspended in an overall pattern of stems and leaves. Parallels with metalwork are found in both the motifs and format, as well as the palette--only two colours, similar to inlay or incised decoration. Fantastic beasts and swirling vines would go on to inspire Italian designers working in Lucca and Venice.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 47.15

Featured Object. This green-glazed terracotta coping was part of an immense underground cistern built by the Almohad Empire in Sidi Bou Othmane, in the mountains north of Marrakech. The water infrastructure relied on seasonal wadis that were dammed in part and connected to cisterns by extensive canalization. The cistern itself also included a settling basin, to remove alluvial deposits from the water. Archaeologists have found copings for the pillars that help the ceiling of the cistern in place -- about 65 in total to date. Many, such as this one, are stamped or carved and then glazed in green. The scale of the cisterns, and corresponding infrastructure are in part explained by the importance of agriculture in this region. But scholars also argue that Sidi Bou Othmane is probably the medieval town of Tounin, an important stop on the road between Marrakech and Fez, which also had a caliphal residence and extensive gardens. With water, a temporary stopping point became an oasis of sorts.

Featured Object. Depending on your perspective, the stamp right in the middle of this embroidered linen towel either adds to its historical interest, detracts from its aesthetic appeal, or both. The embroiderer stitched the towel in a way that motifs looked the same on the front and the back--so the textile was double-faced. This type of technique was found around the eastern Mediterranean and Ottoman world starting probably in the eighteenth century and was well suited to towels, napkins, and wrappers, in which both front and back might be visible at the same time--when folded or hung from a rack or rail. In Greek, the technique is called Tsevres. This one was apparently made on the island of Lesvos in the late 19th century, which was under Ottoman control. And it was also apparently sold or exported beyond the embroiderer's immediate family: the stamp tells us that it passed an inspection point, whether for local taxation or for export to another place.

Athens, Museum of Modern Greek Culture. Gift of Penelopi Ragavi.

Featured Object: Kesi! Tapestry weaving with such fine materials is next-level. A tiger chases a deer through an enchanted forest, on both sides of the fabric, all made of silk and gold. This is only a detail of a longer piece; colleagues in Cleveland suggest it was made as yardage for clothing but ended up used as a cover for leaves of text. It was probably made in China (though it is not entirely clearly where), and the motifs are selected from a number of sources, by artists who were clearly having a ball.

Kesi, silk and gold thread, ca. 1000s or 1100s.

Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. no. 1988.100.

Featured Object. Cotton tabby (plain) weave, block printed. Egypt, early Mamluk period, ca. 1200s or 1300s. This cotton survived quite some time, probably as a result of being discarded or otherwise buried in one of several sites in Egypt that preserve textiles, ceramics, and papyrus alike, Fustat and al-Bahnasa (Oxyrynchus) among them. Artisans in Egypt has been using block-printing techniques on paper from around the year 1000, including for amulets and playing cards. The transfer to textiles might be around the same time, and was also perhaps spurred by the popularity of printed cottons coming from India via the Indian Ocean and Red Sea trade, which itself has left archaeological evidence on the coasts of Egypt and Sudan. In this case, the curators at Cleveland have suggested that the fish is freshwater, perhaps also native to the Nile.

Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. no. 1929.845

Licensed under Creative Commons.

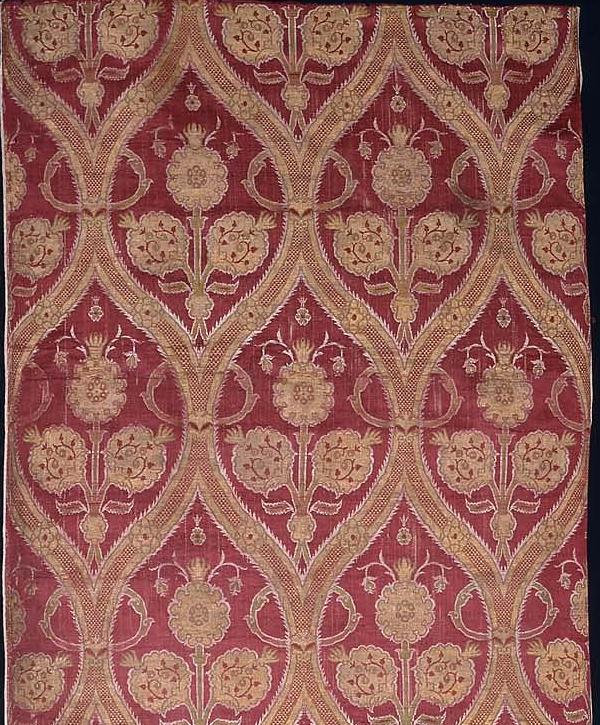

Featured Object. A length of silk textile, in the lampas structure, which combines a satin ground with a twill. In this case, the (warp-faced) satin is crimson and the (weft-faced) twill is gold and green. Many textiles from the Ottoman Empire use a particular type of metal thread know was kılabdan (or kılaptan, etc), made by artisans in workshops attache to the imperial mints -- meant to ensure the close control of precious metal. The workers twisted metal foil around a silk core to make this thread. Yellow silk was combined with silver-gilt, white silk was combined with silver -- to give stronger impressions of gold and silver. In the motif, some people see seed-pods, others see pomegranates and leaves.

Silk and metal foil-wrapped silk thread, satin and twill lampas, known as kemha. Ottoman Empire, probably Istanbul or Bursa, ca. later sixteenth or seventeenth century. Boston MFA, inv. no. 24.148.

Perfectly balanced symmetries and asymmetries--roundels and fields of flowers in crimson and scarlet--show that the women who worked this textile were also master designers. They elaborated on motifs from a number of sources, including other embroideries, ceramics, and printed cottons, turning them into something original and visually cohesive. Not to mention striking. Silk embroidery on cotton tabby (plain-weave) ground, Tajikistan, probably early 1800s. Cleveland Museum of Art, inv. no. 1916.1311. Licensed under Creative Commons.

Featured Object Bird is the word. This is a compound textile --- a structure that uses more than one warp and/or one weft--woven from silk threads. The high-res image shows that it is weft-faced. In this case, too, the color variations that created the pattern come from changes in which weft is pulled to the surface. As she or he raised and lowered the warp threads and inserted the wefts, the weaver was following a sequence that had been set up ahead of time--allowing the perfect repetition of each bird and tree. The pre-programmed apparatus that allowed the perfect repeat also mechanised the process, allowing swifter work--though it did require another worker to manoeuvre it during the work. While most pictures in books or online tend to crop the frayed edges, they are useful tools for scholars interested in materials and technology, and might also tell us about how this was used at some point or another. As for the birds...

Featured Object. This dish sports an arrangement of three vases full of flowers -- a depiction of elegance and luxury painted on what might be considered a utilitarian object. The middle vase appears to sit on a small wooden table or chest, itself decorated with more flowers. The palette is limited, which makes all the flowers unlikely shades of blue, even the carnations and tulips. But veracity was never the point, but rather style. And the dish itself was used as an object of display: two holes drilled in the foot before it was glazed, and presumably to accommodate wire or twine for hanging, probably tell us that the dish was intended for display, Dish, stone paste ceramic underglaze painted. Ottoman Empire, probably Iznik, and dated to the first part of the sixteenth century. Washington, D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, 1955.8. Fair Use for Educational Purposes.

Featured Object. While flowered brocades and crimson velvets are arguably the most famous of Ottoman luxury textiles, weavers made other kinds of objects, some of them for specific uses. This is a compound weave that was specifically made for use in the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire, though its material and weave structure is identical that of the flowered brocades. Its designers modelled the seraphim (those little be-winged heads) on those found in manuscripts, architectural decoration, and probably printed material, as well as other textiles including embroidery. And it was also no doubt luxurious and expensive ... the gold thread still glitters, around three hundred years later.

Detail, kemḫā made for the Armenian community. Silk and metal thread, lampas weave. Probably Constantinople or Bursa, ca. 1550–1700. Athens, Benaki Museum, 3864. Fair Use for Educational Purposes.

Featured Object. Knotted wool pile carpet with cotton warps and wefts, and with additional gilt- and silver-metal thread. This carpet is associated--by its materials and weave-structure as well as its palette, format, and motifs--with the new Safavid capital of Isfahan and the Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas. He has been shown to have encouraged carpet weaving and other crafts there. Many were used in his new palaces and in other residences of the Safavid elite, but some were also traded to Europe and to Poland especially.

Iran, maybe Safavid Isfahan, ca. 1600-1625. Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1926.533.