COURSES

1976/77-2021/22

This section reviews the principal courses I taught at UVa from the Fall of 1976 until the Spring of 2022. UVa hired me for a one-year lecture position for the fall of 1976. During the academic year 1976-77, I applied for and was hired as an Economic Anthropologist in a tenure-track position. Since I was still writing my dissertation my official status didn’t change until I completed my dissertation, in the Spring of 1978. I was then an Assistant Professor until I received tenure in 1983. I was promoted to (full) Professor in 1992.

Although the Anthropology and Sociology Department had been producing Anthropology PhDs for nearly a decade, I joined it and moved into Brooks Hall shortly after the Department separated from Sociology (and Cabell Hall) and just after it and the University resolved to create a major PhD-granting Anthropology Department. There is a story here. One of my Princeton professors, Steve Barnett, told us to ask the dean at our job interviews what he—only hes then—thought of the Anthropology Department, its future etc. So, I asked him. He told me that if it was up to him there wouldn’t be an Anthropology Department… But it wasn’t up to him. Then UVa’s English Department ranked amongst the top three in the country, and that department told the dean they wanted ‘Lévi-Strauss,’ ‘Clifford Geertz,’ or ‘Victor Turner’ at UVa. Then, late 1970s, the ‘Anthropology’ those names represented all but centered Western intellectual life. Fairly soon after that Victor Turner came here, in fact shocking UVa’s administration—'He came to be with them?’

Undergraduate teaching, graduate instruction, and research, in various orders of significance, guided our activities (families and public service were also credited and important to some of us…In the 1980s and early 90s I devoted hundreds of hours to Charlottesville’s youth soccer program, SOCA). Our teaching load was, as it remains, two courses/semester with, initially and proverbially, half of those at a graduate level, half at an undergraduate level. Courses were additionally and informally defined as ‘service to the department’ versus one’s own area of research. Although I took and enjoyed early turns at the proverbial Anthropology 101, Introduction to Anthropology, I was never good at creating large, popular courses. But I created several middle undergraduate courses at what was labeled the 300, then 3000 level. And my usual set was one graduate and three undergraduate courses/academic year. Since I was hired as an economic anthropologist, I soon began teaching, almost yearly, the graduate level 522/5220, Economic Anthropology as well as, by the late 1970s a course called Everyday Life in America (355/3155). For over four decades it had been understood that any willing faculty member would now and again take a two-year turn teaching one of the two ‘history of theory’ graduate courses (over my decades in the Department there was usually at least one undergraduate course for Anthropology Majors of a similar persuasion; these were also traded among faculty). Early in my career I had success teaching the second semester of these, running from roughly The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) to the present. Although I preferred that course, during the second half of my career I only taught it three times, instead taking turns teaching the first half, usually the history of social theory from the 16th or 18th century up to about 1940. Since I did not consider myself a student of the discipline’s history, and several faculty members were, I never particularly enjoyed that course.

Herewith a fuller account of my principal courses, their times and rationales.

Anthropology 355/3155: “Everyday Life in American” or “Introduction to Everyday Life in America” or “Transforming Everyday Life in America.” 1978-Fall, 2021. Originally a 4-credit course with a required Discussion section then reduced to a three-credit course. Eventually the discussion section was dropped—that was unfortunate for the undergrads and the graduate teaching assistant.

I loved this course, grew up with it, and for perhaps 70-90% of the students who took it, created something they never forgot. In our course catalogue it was billed as an ethnography course; it went along with others devoted to Africa, Oceania, South America and the Asias. Theory was subordinated to learning about a place. The course was a writing course, eventually classed as a 2nd Writing course. For the 2nd Writing requirement students had to write 20 pages in at least two assignments; in my course there were 3-6 writing assignments; most students wrote 25 or more pages. The written assignments were drawn from questions I posed to the assigned readings, the first requirement engagement with the ethnographic data at hand, the subordinate requirement a consideration of the theoretical material I spun out in relationship to the ethnography. Motivations for this course were complex, intersecting developments in the discipline as well as my own intellectual needs. Disentangling their order, here is an analytical description of the course origins and its flow through time.

A). When I entered Anthropology in the late 1960s and early 1970s the discipline primarily focused on non-Western societies. Attempts to look at our own social system were sporadic, often teasing, or devoted to some conceived anomaly or relative isolate; none of my teachers were interested in Lloyd Warner’s attempt to turn the trained gaze of Anthropology onto our own society. All this was beginning to change, for me at least, with the intersection of David Schneider’s American Kinship work, Dumont’s passage from India to the West and a French-inspired reading of Capital. My course harnessed this change.

B). I started doing my dissertation research in 1973 in the northeast corner of the Kula Ring, one of the discipline’s classic places for illustrating how exchange organized societies. And my theoretical commitments were to what was called “exchange theory.” This, for me, synthesized Gregory Bateson and Lévi-Strauss. It was then understood that the anthropologist’s first duty was to understand the life people thought they lived. Not intending to be paradoxical, I was somewhat frustrated by the fact that Muyuw people really didn’t locate what they were doing in “exchange.” For them, I soon realized, everything was about making people, their names and things, not exchanging, although they did plenty of that. Fortunately for me, my then principal graduate professor, Martin G. Silverman, was converting from his mixture of Parsons, Radcliffe-Brown and David Schneider to the latter and the Marx then coming out of France. He wrote me about his learning while I was on Muyuw, posing pointed questions from my fleeting ethnographic descriptions. This facilitated the important metaphoric switch from “exchange” to “production.” I had read Four Marx, a bit of Marcuse, and other heavies late in my undergraduate and early in my graduate career. But then, in the Anglo-French anthropology I was taught, nobody seriously read Capital; Marvin Harris’s mechanical materialism dominated what there was of Marxism then. Silverman’s careful reading made me realize I needed to understand Marx. He was also coming to terms with the fact that his own Disconcerting Issue had swallowed Schneider’s American Kinship whole, i.e. without realizing the ethnographic contexts – for example, the cultural process of locating social realities in contract theory—of the synthesis Schneider created. So, I got into that time’s version of Marx realizing it could not apply directly to the Kula Ring. How then to read Capital? I could only accomplish this by locating my understandings in a deepening view of the US variant of the capitalist mode of production. Anthropology 355/3155, Everyday Life in America, enabled that reading.

C). Its title: I hopped on a bandwagon I thought was nonsense. Henry Lefebvre’s Everyday Life in the Modern World was central to some discussion in the 1970s and was borrowed for the Barnett and Silverman collection IDEOLOGY AND EVERYDAY LIFE: Anthropology, Neomarxist Thought, and the Problem of Ideology and the Social Whole. I used the title but never meant it. The Durkheimian tradition, arguably rearticulated for Anthropology in different ways by Lévi-Strauss, Evans-Pritchard and Victor Turner’s work, taught us that if you could not figure out what social systems were doing in their rituals and other important collective representations you didn’t understand them. When I started the course baseball still had its grip as the United States’s major athletic structure (this changed quickly). So, not entirely seriously, I assumed that if I couldn’t show how Marx’s understandings of the categories and relations in our society helped make sense out of the place of baseball in US culture, then Marx was wrong. The operating theory here was that major rituals synthesize important dimensions of a social systems fundamental principles. Hence for perhaps 15 years Roger Angel’s classic Five Seasons played a prominent role in the course (Throughout the course’s history there was usually a lecture devoted to sports, often synched with a calendrical discussion. After I stopped assigning his work, as often as not, that lecture read from Five Seasons’s “Agincourt and After,” Angel’s synopsis of the 1975 World Series.). ‘Baseball’ helped me and the students learn about the complexities in the relationship Marx built into his idea of the commodity form and the dialectical values in Western –and their US version—culture’s exchange spheres. Realizing how complex that form was, that it was a complex social fact, cured me of ever thinking I could use “commodity” for other social systems without understanding a lot of other things, most of which varied greatly from the West. Throughout much of the discipline, however, the term was commonly employed—incorrectly from my point of view. I return to this translation problem in my discussion of my Graduate Economic Anthropology course, A522/A5220. But I note that my course was first a test to see if the complex order Marx created in Capital was plausibly correct for the ensemble that became and remains the United States; and then to see how far I could push it as an analytical model, along with many other anthropological models. Although I’m not sure students ever got the point, early in the course structure when I lectured about Marx’s primary circulation forms, M-C-M’/C-M-C’, I showed how the analogous forms in the Kula were very different (They entail a more complex structure and dialectic between what can be called material and spiritual values, the discussion of which was designed to foreshadow the description of class relations in Anti-bellum US culture, as Wallace’s Rockdale showed them.).

D). By the time I returned from my dissertation fieldwork in late 1975 Princeton’s anthropology department had been turned inside out. Martin Silverman, my dissertation committee chair, had moved to the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. On my way back to Princeton from Minneapolis (my parent’s home and where my wife started an Ma in American Studies at the University of Minnesota and had our first child) I stopped to see him. Martin gave me a copy of the second chapter which he and Barnett were writing for the above-mentioned book: “2. Separations in Capitalist Societies: Persons, Things, Units and Relations.” The chapter remains a great synthesis of Schneider’s American Kinship, Dumont’s initial essays on his movement from ‘India’ to the ‘West,’ and the Marx of The Grundrisse and Capital, considerably mediated by Ollman’s Alienation. That chapter became and remained the intellectual core for my course. Although not just because of it, for most of the 40-plus years I taught the course students were required to read the first two Parts of Capital and Dumont’s 1965 essay “The Modern Conception of the Individual: Notes on its genesis and that of concomitant institutions” (until its slightly revised version appeared in 1986, “The Political Category and the State from the Thirteenth Century Onward”). Although my usage of Capital did not change much throughout the course’s history--the structure of the course always allowed me to add the remainder of  Capital, Volume I, and much of Volume II, in lectures—Dumont’s essay often changed its appearance as events and movies came and went. Initially, Dumont’s discussion of Locke and “private property” enriched my understanding of the anti-hero in Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy. Later as other matters engaged the US (e.g. 9/11), it helped me show how external threats repeatedly gave US citizens their only or primary sense of the social whole; sports teach that structure.

Capital, Volume I, and much of Volume II, in lectures—Dumont’s essay often changed its appearance as events and movies came and went. Initially, Dumont’s discussion of Locke and “private property” enriched my understanding of the anti-hero in Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy. Later as other matters engaged the US (e.g. 9/11), it helped me show how external threats repeatedly gave US citizens their only or primary sense of the social whole; sports teach that structure.

E). Before I went to see Silverman in London, Ontario, my wife, Nancy Coble Damon, introduced me to one of her University of Minnesota American Studies professors, the  intellectual historian David Noble. The encounter changed my intellectual life. Classable as a “Progressive Historian,” in 1965 Noble published HISTORIANS AGAINST HISTORY: The Frontier Thesis and the National Covenant in American Historical Writing since 1830. It was a critique of the writing of American history beginning with George Bancroft (1800-1991), ending with Daniel Boorstin (1914-2004). The book’s plotline was that now, having shown the mythological character of the United States’ secular priests, its great historians, we could begin to write our history. However, the next year The Savage Mind and Purity and Danger appeared and from them Noble realized he had written something considerably more interesting, effectively the intellectual infrastructure of a way of being—in Ruth Benedict’s parlance, a fundamental pattern of life. The book became a stable in my course for at least 15 years and proved an apt accompaniment to Will Wright’s Sixguns and Society. I taught that book –Sixguns –until roughly 1990; by that time only the students’ grandparents lived in Westerns, and Elizabeth Traube’s Dreaming Identities became an apt replacement. I continued to lecture from the Noble book in various course sections. After the 9/11 movie United 93 appeared, I returned to assigning Noble’s chapter on Bancroft: “GEORGE BANCROT: NATURE AND THE FULFILLMENT OF THE COVENANT.” That chapter outlines what Noble calls “historical dramas;” Paul Greengrass’s United 93 reproduces that form, as do many successful US movies, almost regardless of genre. This fact facilitated teaching important threads in anthropology since Victor Turner and Anthony Wallace constructed similar ideas in their work. (e.g., Turner’s “social dramas,” the “plot” in Wallace’s Rockdale.) Incidentally, I realized I was not off-base in picking up Noble’s work when I passed a copy first to Steve Barnett, then Roy Wagner. Barnett found it useful for thinking through the problem of sacrifice he and Martin Silverman needed to embed in their “Separations” chapter; Wagner and Noble started a conversation by phone and letter that lasted for about a decade. During one of my wife’s 1975 summer classes, Noble pulled out Wagner’s Invention of Culture and told the class ‘I bet none of you have read this book or heard of this man.’ I corresponded with Roy while doing my dissertation fieldwork, so Nancy was an exception to Noble’s feat of introducing an important personage to the humble students. Noble was a serious student of anthropology. My intellectual family tree had no place for Boas but Noble dismissed my dismissal. He told me “structuralism” and the “neo-marxist” wave then washing the academy wouldn’t make it in the United States because both emphasized complexity; he felt Geertz’s work replicated more familiar US thought patterns. His prediction proved correct. About most Marxists in the United States, he referred to them as “Saints” and said they were reproducing a familiar meme in US culture, showing that in fact we had one and we should dispense with it. I believe he was, and remains, correct about that; showing that we had a hierarchy that should be dispensed with was never the purpose of the course in which Noble’s work played an enormous role.

intellectual historian David Noble. The encounter changed my intellectual life. Classable as a “Progressive Historian,” in 1965 Noble published HISTORIANS AGAINST HISTORY: The Frontier Thesis and the National Covenant in American Historical Writing since 1830. It was a critique of the writing of American history beginning with George Bancroft (1800-1991), ending with Daniel Boorstin (1914-2004). The book’s plotline was that now, having shown the mythological character of the United States’ secular priests, its great historians, we could begin to write our history. However, the next year The Savage Mind and Purity and Danger appeared and from them Noble realized he had written something considerably more interesting, effectively the intellectual infrastructure of a way of being—in Ruth Benedict’s parlance, a fundamental pattern of life. The book became a stable in my course for at least 15 years and proved an apt accompaniment to Will Wright’s Sixguns and Society. I taught that book –Sixguns –until roughly 1990; by that time only the students’ grandparents lived in Westerns, and Elizabeth Traube’s Dreaming Identities became an apt replacement. I continued to lecture from the Noble book in various course sections. After the 9/11 movie United 93 appeared, I returned to assigning Noble’s chapter on Bancroft: “GEORGE BANCROT: NATURE AND THE FULFILLMENT OF THE COVENANT.” That chapter outlines what Noble calls “historical dramas;” Paul Greengrass’s United 93 reproduces that form, as do many successful US movies, almost regardless of genre. This fact facilitated teaching important threads in anthropology since Victor Turner and Anthony Wallace constructed similar ideas in their work. (e.g., Turner’s “social dramas,” the “plot” in Wallace’s Rockdale.) Incidentally, I realized I was not off-base in picking up Noble’s work when I passed a copy first to Steve Barnett, then Roy Wagner. Barnett found it useful for thinking through the problem of sacrifice he and Martin Silverman needed to embed in their “Separations” chapter; Wagner and Noble started a conversation by phone and letter that lasted for about a decade. During one of my wife’s 1975 summer classes, Noble pulled out Wagner’s Invention of Culture and told the class ‘I bet none of you have read this book or heard of this man.’ I corresponded with Roy while doing my dissertation fieldwork, so Nancy was an exception to Noble’s feat of introducing an important personage to the humble students. Noble was a serious student of anthropology. My intellectual family tree had no place for Boas but Noble dismissed my dismissal. He told me “structuralism” and the “neo-marxist” wave then washing the academy wouldn’t make it in the United States because both emphasized complexity; he felt Geertz’s work replicated more familiar US thought patterns. His prediction proved correct. About most Marxists in the United States, he referred to them as “Saints” and said they were reproducing a familiar meme in US culture, showing that in fact we had one and we should dispense with it. I believe he was, and remains, correct about that; showing that we had a hierarchy that should be dispensed with was never the purpose of the course in which Noble’s work played an enormous role.

F). In February, 1976, after stumbling around my fieldnotes the previous fall, I went to New York to see another professor dismissed from Princeton while I was in Muyuw: Vincent Crapanzano. Vincent was supposed to be home but in fact was not in his apartment on Central Park West when I arrived. His wife, Jane Kramer, let me in (When I entered a subway near Penn Station for the passage to Vincent’s, a mangled body was being scrapped off the tracks from

either a suicide, murder, or dumb luck; I shuttered with the idea that Crapanzano was the scrappings I’d witnessed but said nothing to Jane.). In 1971 or 72 Crapanzano had had our class to New York for an evening, so I’d already met his wife, and had known that she was a reporter for The New Yorker, in fact, its European correspondent. But that February she had just returned from a year in the Texas Panhandle. She thought she needed to come home, to see what it, home, really was. And what better place than Texas? Hence, she was working through how she was going to write up what turned out to be two successive “Profiles” for The New Yorker. She knew she was creating a kind of anti-hero inside the Frontier Thesis anchoring American mythology and I talked to her about what she was doing in relationship to Noble’s book. I used The New Yorker Profiles at the beginning of my course in its first or second year. They re-appeared in her book, The Last Cowboy, a 1981 National Book Award for Nonfiction. It took a place in my course—in the beginning until 2016—right up through the last time I taught it, Fall, 2021. Kramer modeled herself after anthropology’s intensive engagement with its subject matter. The book is an impressive feat. Its simple language paints a picture of a struggling life in the context of the last century of US history. The story’s central character lived inside the Western movies that defined the middle 50 years of the 20th century. Yet he was being pulled into the role of an assembly-line worker as the cattle industry transformed after WWII into the Fast-Food business. The book embedded sociology, mythology, capitalist history. I had it start the course because it seemed so simple…and had to tell each class to reread it once the course was over so they could realize how much was packed into it. With it I taught about the aesthetics of American cosmology; the sociology and cosmology of exchange as evident in Capital, Chapters 2-6; put in a plug for Kondratieff Long Waves in relation to the use of irrigation wells and the consequent re-organization of the cattle industry; and used Kenneth Burke’s “dramatic pentad” for talking about the difficulties in thinking about social forms. The Last Cowboy begins with the “scene” of US culture; by contrast, Capital begins with “purpose.” Once Rush Limbaugh began dominating the airwaves, I realized how the torment he exemplified was prefigured in the cowboys Kramer had described. The book became more than a Prelude. And when Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation appeared in 2001 a ‘beautiful’ historical complement arrived. Students could see how these forms played out through time.

either a suicide, murder, or dumb luck; I shuttered with the idea that Crapanzano was the scrappings I’d witnessed but said nothing to Jane.). In 1971 or 72 Crapanzano had had our class to New York for an evening, so I’d already met his wife, and had known that she was a reporter for The New Yorker, in fact, its European correspondent. But that February she had just returned from a year in the Texas Panhandle. She thought she needed to come home, to see what it, home, really was. And what better place than Texas? Hence, she was working through how she was going to write up what turned out to be two successive “Profiles” for The New Yorker. She knew she was creating a kind of anti-hero inside the Frontier Thesis anchoring American mythology and I talked to her about what she was doing in relationship to Noble’s book. I used The New Yorker Profiles at the beginning of my course in its first or second year. They re-appeared in her book, The Last Cowboy, a 1981 National Book Award for Nonfiction. It took a place in my course—in the beginning until 2016—right up through the last time I taught it, Fall, 2021. Kramer modeled herself after anthropology’s intensive engagement with its subject matter. The book is an impressive feat. Its simple language paints a picture of a struggling life in the context of the last century of US history. The story’s central character lived inside the Western movies that defined the middle 50 years of the 20th century. Yet he was being pulled into the role of an assembly-line worker as the cattle industry transformed after WWII into the Fast-Food business. The book embedded sociology, mythology, capitalist history. I had it start the course because it seemed so simple…and had to tell each class to reread it once the course was over so they could realize how much was packed into it. With it I taught about the aesthetics of American cosmology; the sociology and cosmology of exchange as evident in Capital, Chapters 2-6; put in a plug for Kondratieff Long Waves in relation to the use of irrigation wells and the consequent re-organization of the cattle industry; and used Kenneth Burke’s “dramatic pentad” for talking about the difficulties in thinking about social forms. The Last Cowboy begins with the “scene” of US culture; by contrast, Capital begins with “purpose.” Once Rush Limbaugh began dominating the airwaves, I realized how the torment he exemplified was prefigured in the cowboys Kramer had described. The book became more than a Prelude. And when Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation appeared in 2001 a ‘beautiful’ historical complement arrived. Students could see how these forms played out through time.

Maurice Godelier invited me to Paris in the spring on 1982 and while there I met Jane and Vincent (who had just finished his South African research) one evening in their apartment. She then described the characters in the book and their fates since her time with them: ‘Its all true,’ one of them wrote her and she also received letters from Americans all over the country describing how their lives were described in that “representative anecdote”—a Kenneth Burke concept—of America Life. Yet this became only the first of several conversations—face to face, by letter and email—we had about the book, its personages, and the insights which could be had from it. Probably the last of these conversations was in the winter of 2017 when my wife and I visited NYC. My conversations with Jane were always bundled with encounters with Vincent whose psychological orientation was foreign to my own; but just the same, he always introduced a depth which has remained a gnawing but productive presence. Muyuw people had a psychological depth—that is meant as a cultural, not a psychological fact—that most of my ethnographic interests barely touched. Crapanzano highlighted, for me, the mysteriousness of time, personal and collective.

G). The course facilitated working through two other problems reasonably evident as I began my teaching career. Since most anthropological models had been created for “primitive” or “non-western” societies, and there was a presumed (but largely unexamined) difference between “Them” and “Us,” how applicable were these models to Western societies? The existence of ‘primitive thought and/or action’ amidst modern society used to be dealt with as a matter of survivals, fraternities and the like. Yet functionalism’s truths had made that strategy both irrelevant and incorrect. So, one aspect of the course became devoted to seeing the limits of the application of various models initially meant for other places and other times. One aspect of that involved using models of “sacrifice”—drawn mostly from Nuer Religion and The Savage Mind—on various aspect of US culture. Some of this became realized in two recent publications: 2016b “The problem of ‘Ultimate Values:’ Charting a Future in Dumont’s Footsteps.” In Puissance et impuissance de la valeur: L'anthropologie comparative de Louis Dumont ed. Cécile Barraud, André Iteanu Et Ismaël Moya. CNRS Editions. Pp. 219-235. And 2016c “THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE DEAD: The place of destruction in the organization of social life, which means hierarchy.” Social Analysis, Volume 60(4): 58–75. DOI: doi.org/10.3167/sa.2016.600404.). The person who replaced the official chair of my dissertation committee, Peter Huber, over the course of our relationship added much to this. Using the Evans-Pritchard model of sacrifice he generated a charming and insightful analysis of birthday rituals in the US which I used in the course; much later he created an analysis of advertising for things like lawn mowers borrowing convincingly from Marcel Mauss’s discussion of the Maori idea of hau, an almost mystical notion inherent in and apparently animating things.

Another usage involved applying Paul Bohannan’s ideas about Tiv exchange spheres to the circulation forms Marx outlined in the first two Parts of Capital. This meant understanding, then discounting the original historical contexts for the creation of those ‘Anthropological’ ideas (principally the idea that exchange spheres didn’t exist in Western societies), a matter about which I had an exchange with Raymond Firth (who supported my usage). This work backgrounded almost all my significant publications about Muyuw, my research locale in the Kula Ring, written from the late 1970s to about 1994.

By the time this course started–late 1970s—it was also clear that if you were so inclined doing a structural or symbolic analysis on those non-western societies was possible and created significant insight. Yet, in those times, we had very little historical depth on those societies. So how would these analyzes hold up through time? Then the received wisdom—mostly nonsense—was that Lévi-Strauss’s structuralism was “synchronic” and incapable of dealing with historical change or transformation. (The year before I began my fieldwork Nancy Munn was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. We occasionally met. And one of the issues we talked about was this problem—how symbolic analyzes could work through time when we lacked in-depth historical data; I guessed that her final years devoted to New York’s Central Park was, in part, her attempt to deal with that issue.)

This problem could be faced with a well-designed course on US culture because if one wished, as I did, the course could be constructed through upwards of three hundred years of history. A comment David Noble dropped on me during our first meeting in 1975 had a bearing on this. I had asked him about “religion” in America early on and he looked at me and said something like "There wasn’t any."

I usually started the course with Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy accompanied by Marx and Dumont because I wanted to feature problems of ‘where to begin’ and the idea of social forms (This plan changed when the appearance of Donald Trump for the 2016 Presidential election created a different urgency.). Then the course turned to its historical thread. Effectively it ran from about 1790 to the present. And I was lucky. As I was starting this course the first people trained in the emerging field of “American Studies” were publishing monographs based on their dissertations. The first one I deployed was Dickson Bruce’s AND THEY ALL SANG HALLELUJAH, a discussion of the rise of the Baptist and Methodist  churches in the South from about 1800 to 1830. As a piece of history (Bruce’s synthesis derived from what Eugene Genovese represented), the book didn’t break any ground, but two of its chapters created sophisticated and effectively anthropological accounts of camp meetings as rituals and effective vehicles for the transformation of apparently individual selves (Dumont’s ideas could be applied to these as could ideas about alienation as it appeared in the more interesting literature departing from Marx). Then appeared Paul Johnson’s masterpiece on Rochester, New York, A SHOPKEEPERIS MILLENNIUM. These books engaged me in the writings about what historians understand as The Second Great Awakening, and effectively explain how the US got religion (explaining Noble’s statement that the US didn’t have any [until this time]). Eventually these two books helped me create a contrast between the South and the North. It became fun to see how far I could push it—as Production Departments (Capital, Vol. II), incipient moieties with fractal realizations across the culture and its spaces? The two authors describe very different religious orientations. Being far from an expert on these times, I always asked UVa historians if I had the facts right, the question being was I setting people up for future good scholarship—I was. For several decades I encouraged non-Anthropology Majors and younger students to read these two books; Majors and 4th year students and, often, American Studies Majors, were encouraged Anthony Wallace’s massive historical ethnography, ROCKVILLE, a book that compares favorably to Thompson’s THE MAKING OF THE ENGLISH WORKING CLASS. As with the course at large, Wallace’s book eventually became exceedingly important for my forays into Indo-Pacific technical and ideological structures (e.g. 2008 “A STRANGER’S VIEW OF BIHAR-RETHINKING RELIGION AND PRODUCTION” in Speaking of Peasants: Essays on Indian History and Politics in Honor of Walter Hauser. Edited by William Pinch. New Deli: Manohar Publishers. Pp.249-276. 2012 ‘Labour Processes’ Across the Indo-Pacific: Towards a Comparative Analysis of Civilisational Necessities,” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology Vol. 13(2): 170-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2012.656695).

churches in the South from about 1800 to 1830. As a piece of history (Bruce’s synthesis derived from what Eugene Genovese represented), the book didn’t break any ground, but two of its chapters created sophisticated and effectively anthropological accounts of camp meetings as rituals and effective vehicles for the transformation of apparently individual selves (Dumont’s ideas could be applied to these as could ideas about alienation as it appeared in the more interesting literature departing from Marx). Then appeared Paul Johnson’s masterpiece on Rochester, New York, A SHOPKEEPERIS MILLENNIUM. These books engaged me in the writings about what historians understand as The Second Great Awakening, and effectively explain how the US got religion (explaining Noble’s statement that the US didn’t have any [until this time]). Eventually these two books helped me create a contrast between the South and the North. It became fun to see how far I could push it—as Production Departments (Capital, Vol. II), incipient moieties with fractal realizations across the culture and its spaces? The two authors describe very different religious orientations. Being far from an expert on these times, I always asked UVa historians if I had the facts right, the question being was I setting people up for future good scholarship—I was. For several decades I encouraged non-Anthropology Majors and younger students to read these two books; Majors and 4th year students and, often, American Studies Majors, were encouraged Anthony Wallace’s massive historical ethnography, ROCKVILLE, a book that compares favorably to Thompson’s THE MAKING OF THE ENGLISH WORKING CLASS. As with the course at large, Wallace’s book eventually became exceedingly important for my forays into Indo-Pacific technical and ideological structures (e.g. 2008 “A STRANGER’S VIEW OF BIHAR-RETHINKING RELIGION AND PRODUCTION” in Speaking of Peasants: Essays on Indian History and Politics in Honor of Walter Hauser. Edited by William Pinch. New Deli: Manohar Publishers. Pp.249-276. 2012 ‘Labour Processes’ Across the Indo-Pacific: Towards a Comparative Analysis of Civilisational Necessities,” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology Vol. 13(2): 170-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2012.656695).

For a few years I added to the course the ROCKDALE follow-up, Wallace’s 1987 ST. CLAIR A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town’s Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry. It bridged my early 19th century section to the remainder of the course, which ran from about 1920 to the present. Wallace’s dealing with the coal industry and its characters, drawing on his and other’s (including Johnson’s) discussion of the Second Great Awakening, is not only subtle but provocative. His discussion of the Molly Maguires and the Pinkerton private police force created historical parallels with Southern transformations of the time—lynching and the Jim Crow epoch—and foreshadowed the transformation of those forms into the likes of the FBI and CIA in the 20th century. I vainly hoped I could get some student to take this on as a Senior Research Project or the like…This work also surfaced in my 2016 sacrifice paper noted above.

For a few years I added to the course the ROCKDALE follow-up, Wallace’s 1987 ST. CLAIR A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town’s Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry. It bridged my early 19th century section to the remainder of the course, which ran from about 1920 to the present. Wallace’s dealing with the coal industry and its characters, drawing on his and other’s (including Johnson’s) discussion of the Second Great Awakening, is not only subtle but provocative. His discussion of the Molly Maguires and the Pinkerton private police force created historical parallels with Southern transformations of the time—lynching and the Jim Crow epoch—and foreshadowed the transformation of those forms into the likes of the FBI and CIA in the 20th century. I vainly hoped I could get some student to take this on as a Senior Research Project or the like…This work also surfaced in my 2016 sacrifice paper noted above.

H). About the Anthropological models: Although my dissertation research experience on Muyuw forced me into reconsidering my relationship to the Bateson/Lévi-Strauss synthesis I started with, it did not change some generalities. In POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF HIGHLAND BURMA Edmund Leach told us that what anthropologists mean by “social structure” is what their informants usually mean by their systems of debt. In Muyuw, happily, the word vag can be translated accurately as both “make” and “debt.” So, a major question for me became the degree to which I could orient the course to US debt structures, linking it to productive anthropological  analyzes. That task was made easy by the appearance of Constance Perin’s EVERYTHING IN ITS PLACE (1977); I used it, or its great Chapter Two “The Ladder of Life: From Renter to Owner,” for the whole course, its closing years justifying the reissue of the book as a Princeton Classic. The course’s early history was, of course, the end of a phase in US culture running from circa 1930 to 1980, the time during which the country became organized around 30-year mortgages, suburban spaces, automobiles, and the eventual crises –Savings and Loans among others—that transformed aspects of that set of ideas. A graduate student from the late 1970s and early 1980s wrote a dissertation about the mortgage industry. Although her work was never realized professionally, her experiences traveled with the course through its decades, and eventually were nicely augmented by Michael Lewis’s writings, Liar’s Poker from the moment it appeared, The Big Short following the 2007-08 financial crisis. Over the latter book I re-established contact with Perin, only later realizing that she was close to death (d. 2012). But her work from my course lives on as a UVa graduate student, partly from the course, became engaged in research on the financing of various Green activities; and she is being advised by an old student from the 1980s who himself went into high finance and had a telling experience in the 2007-08 crisis. The course’s intent to explore the historicity of US culture lives in multiple ways.

analyzes. That task was made easy by the appearance of Constance Perin’s EVERYTHING IN ITS PLACE (1977); I used it, or its great Chapter Two “The Ladder of Life: From Renter to Owner,” for the whole course, its closing years justifying the reissue of the book as a Princeton Classic. The course’s early history was, of course, the end of a phase in US culture running from circa 1930 to 1980, the time during which the country became organized around 30-year mortgages, suburban spaces, automobiles, and the eventual crises –Savings and Loans among others—that transformed aspects of that set of ideas. A graduate student from the late 1970s and early 1980s wrote a dissertation about the mortgage industry. Although her work was never realized professionally, her experiences traveled with the course through its decades, and eventually were nicely augmented by Michael Lewis’s writings, Liar’s Poker from the moment it appeared, The Big Short following the 2007-08 financial crisis. Over the latter book I re-established contact with Perin, only later realizing that she was close to death (d. 2012). But her work from my course lives on as a UVa graduate student, partly from the course, became engaged in research on the financing of various Green activities; and she is being advised by an old student from the 1980s who himself went into high finance and had a telling experience in the 2007-08 crisis. The course’s intent to explore the historicity of US culture lives in multiple ways.

Although students who took the course in the late 1970s and 80s would recognize its structures from its last two decades, time’s vicissitudes led to significant inputs. The economic thrust of my own intellectual requirements, and the 1980s, brought me to two important studies. One is the journalist Max Holland’s 1989 WHEN THE MACHINE STOPPED, an account of the end of the US dominance of the “machine tool industry’’—the age of leveraged buyouts begins with the episodes Holland described. The other is MORAL MAZES, The World of Corporate Managers, written by the C. Wright Mills-inspired sociologist, Robert Jackall. Although it was not Jackall’s intent, his study of upper-level managers in major US corporations describes qualities Wallace showed in Rockdale and Marx put forth in Capital’s middle Parts. Unfortunately, students found Jackall’s book too depressing for me to continue in the course’s reading list (but it became a book for my Graduate Economic course for any student interested in contemporary society). Holland’s book appeared along with the hollowing out of a major portion of the country, and without doubt GE’s Jack Welch became the business hero of the times that book represents. The book was written and taught by me over the years when PCs were becoming di rigueur; so another view the book afforded was the thought that computers and software were becoming the new machine tools. In either case the book exemplifies transitions one often sees in Kondratieff Long Wave toughs; Lewis’s Liar’s Poker describes the reorganization of financial structures which are also practices that seem to be repeated regularly across times KLW suggestively organize. For a decade or more I followed up these ideas with Lewis’s account of the computer whiz and serial entrepreneur Jim Clark in The New, New Thing (a book I think is superior to Isaacson’s on Steve Jobs for describing a complicated character amidst social transformations). Lewis is unmatched in his ability to write detailed biography, history and, essentially, anthropology, with considerable humor. One year one student wrote a stunning paper pulling together Liar’s Poker, The Big Short, Bateson’s ideas about schismogenesis and Lévi-Strauss’s ideas about temporal trajectories possible in his model of generalized exchange. These books, and papers students wrote from them, led to my curious reaction to Paul Rabinow’s important ethnography, MAKING PCR A Story of Biotechnology, which I used for several years. It is a good piece of anthropology: the anthropologist goes into unknown territory and then writes a coherent, interesting account which tells others a lot—in this case about the origin of an important aspect of contemporary social action. Yet Rabinow suggested that the book, like the discipline should, documents the particularity of practices. In fact, he tells a tale intrinsic to the capitalist mode of production—if one pays attention to its ordering. The book reminded me of Noble’s prediction that both ‘structuralism’ and the neo-marxist input would fail in America, because of ingrained threads in that very culture.

I published my comparison of Muyuw and the Trobriands in 1990. Although I was pleased with the outcome, an ethnography of a place given its self-conscious and informed relation to another, Muyuw people also understood themselves in relationship to other nearby and different cultural forms and I didn’t know how I could describe those transformations in relation to those that depict the Muyuw/Trobriand shift. About that time, I was a reviewer for an article Mark Mosko wrote trying to (re-) deploy Levi-Strass’s canonic formula for myth. Although I toyed with anthropology’s history of analyzing myths in the movie section of my course—Wright’s Sixguns and Society deploys Lévi-Strauss’s ideas about opposition but uses Propp for analyzing movie structures—I never took that formula seriously until I witnessed Mosko’s creative extension. So, I started fiddling, first with movies, then with other social forms. One set of transformations turned contrasts in the religious forms created before the Civil War into the likes of lynching and other forms of violence prevalent after that war. Other experiments suggested how various kinds of criminal activity were transformations of normative social action (often understood in terms of “use value” and “exchange value” as Marx deployed those categories in Capital and I illustrated their usage in US culture). I never succeeded in getting any student to follow up these intellectual games and I was never entirely persuaded by what I thought I was showing. But this chapter in the course’s history confirmed my sense of the productiveness of taking seriously many of anthropology’s ideas for analyzing our own society. It may be noted that this thread in the course developed as a post-modernist critique in the social sciences reached a climax and veered to a nearly complete dismissal of a hundred years of social analytics. This was being done by people who were taking full advantage of the positions they either inherited from that history or succeeded to because of it (Robert Jackall’s Moral Mazes has a witty comment on this moment in the social sciences, suggesting its affinities with the purely prestige games operating in large, corporate bureaucracies—so ‘post-modernism’ as superstructure for the bureaucratic mode of production!). I ignored much of the post-modernist critique, and its follow-ups, because I was learning so much from the intellectual tools I’d received. This led me to think those times’ leaders generated some combination of travesty and tragedy.

I). Along with re-invigorated concerns with the “environment” in US culture at large and my own veer toward environmental research about 1990, a I added a final theme. This was to make a section in the course devoted to “environmental issues.” My idea was not to push a particular perspective; it was to make explicit some time or place’s relationship to explicit environmental action. To a considerable degree, journalists’ writing provided much of my ethnographic material. Early on I came across Blaine Harden’s elegiac account of the damming of the Columbia River, A River Lost, and that book remained a selection for some people to read to the very end (His last book, Murder at the Mission, as did he by zoom, appeared also in the course’s last year.). Timothy Egan’s account of the Dust Bowl in The Worst Hard Time told an important story for a few years, and it was easy to integrate these, and other works, into information Wallace provided in St. Clair. That book’s chapter in American history featured the 19th century’s millenarian cast over a ‘nature’ that was wild and feminine and needed taming, and plundering, for men to be men; much of the 20th century, and not only its dam-making, worked through that miasma until it started caving in on itself (Arguably prefigured in the book and especially the movie Deliverance, which I frequently used in the course’s movie section …one reason for which was its illustration of the strangest twists in Lévi-Strauss’s The Savage Mind, the last two chapters from which I often asked students to read.). Other journalists’ work made brief appearances in the course adding much to me, if not the students too. Among these are Arax and Wartzman’s THE KING OF CALIFORNIA: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire, and Grunwald’s THE SWAMP: The Everglades, Florida and the Politics of Paradise. Eric Rutckow’s American Canopy served some good time as well. Most of these books concerned transformations in infrastructures and they were an important complement to the course’s historical footing, and problem. One of the perspectives here fit back into the use of Capital. For if one took seriously Marx’s elaboration of his sphere of capital, M-C-M’, then one realized that the contradictions in the relationships between “constant” and “variable capital” were going to generate an enormous dynamic. In structuralist terms, there was a lot of ‘diachrony’ inside a ‘synchronic’ form. The course showed that.

Although his view was that of an outsider’s—that is, like an anthropologist’s—Tim Flannery’s uncanny synthesis of North American geological, climatological, biological and human history in The Eternal Frontier eventually supplied a view of Western European action on this land which I brought into the course; occasionally I assigned chapters from the final and 5th Part of his tragedy. Flannery deploys a temporal model for how emigrant species react in new environments; they run through a sequence he discerns as “Founder’s Effect,” “Ecological Release” and “Adaptation,” the latter referring to the time when the organism realizes it must conform to its surroundings. If many of the books just mentioned describe activities in the second of these stages, the third probably begins with Silent Spring; and the writing of the environmental books illustrate the arguments being carried out in the third. Arguably, in many different guises, these are the central political problem of our time. Are we going to continue uncontrolled action on this earth or come to terms with its structures?

J). When Victor Turner arrived in our department in the late 1970s word filtered through that teaching should be subordinated to our writing. Few of us really did that, but this course in a sense practiced such wisdom: I was working through theoretical problems which were designed to enable other work, graduate instruction and my own research and writing. Since enough undergraduates found it stimulating, I could care more about its theoretical and ethnographic content than the numbers of people who sat through it. One example illustrates how this worked. In the late 1970s and early 1980s I used the structure of our elections to illustrate Van Gennep’s rites-of-passage model (which Bruce employed in And They All Sang Hallelujah). Then the outcome of a 1982 Virginia senatorial election baffled me, and not just because my candidate lost. I didn’t understand why what happened happened. As a committed member of our political society, I had one response—work harder for my candidates; but as an anthropologist I had a different obligation, which was to try to figure out what our elections really were and how they worked. Thus began a decade of searching. In 1991 Dumont’s research team (equip), ERASMUS invited me Paris to give lectures on my Kula work. Since by then one of the ideas I was using to analyze our election system/ritual devolved from Dumont’s work, I asked my hosts if I could give a 5th lecture on that work. They didn’t agree until I gave them a draft of the paper to review (Dumont liked it.). I needed this because while filling in some of the material was easy, aspects of the synthesis really needed to be checked by an outsider. Among other things, I discovered many Europeans had an entirely different interpretation of the place of religion in US elections than I did (concerning the use of the Bible in inaugurations; Tim Flannery’s reading of US culture was like the Europeans, effectively saying American thought was pre-Enlightenment). Daniel De Coppet in particular asked questions I couldn’t answer, and every time I returned to Paris we continued discussing fine points of US practices. Long before my conversation with Daniel was finished, he died, and I decided to publish the paper in the Taiwanese Journal of Anthropology (Damon 2003). This was the only thing I wrote in which I favorably cited Clifford Geertz so eventually I sent it to him. He liked it too, I think realizing that three of my four ritual models were “of course,” a fourth, coupling Dumont and Parsons, was interesting but not there yet. It argued that our educational and electoral structures were complementary inversions of one another. (About 2010 I learned that Jonathan Friedman had been using the article in a graduate course, contrasting it with what he knew of European—French and Swedish mostly—electoral politics; he was interpreting the data through the lens of Lévi-Strauss’s chapter “Do Dual Organizations Exist?”, and, I believe, Wallerstein’s discussion of 19th century election systems found in the fourth volume of his Modern World-System set.). The paper’s fourth part was

the only thing I kept working on for the next 15 years, eventually adding to the course syllabus the Washington Post journalist Robert Kaiser’s history of lobbying, SO DAMN MUCH MONEY.

Then 2016 arrived and I knew I had to return to the synthesis to see what, if anything, the Trump phenomena raised for my interpretations. I started that fall’s course –and all subsequent versions—with the election paper, adding to my reading, and some of the students’, recent books about Buffalo Bill Cody, P.T. Barnum and others. Trump has plenty of 19th and early 20th century predecessors, but they never became politically significant. What is changing? I started that rethinking in lectures in China during the summer of 2016. One of my hosts, Tang Yun in the West-South Nationalities University, headed to Oxford for the 2016-17 academic year and participated in the anguish Trump’s victory created for many people there, especially, of course, the Americans. She told her head, Elisabeth Hsu, how my use of classical anthropological ritual models on US elections shed a different light on the practices. That resulted in a modified re-publication of the piece (Damon 2017). In the fall 2016 course itself one of the students wrote a brilliant paper comparing Trump’s mode of action to the ministers who led the Southern Camp Meetings described in Bruce’s book, And they all Sang Hallelujah. The course lives.

This synthesis neglects all but two of the marvelous papers students wrote throughout the course’s history, many of which I’ve kept. It was a joy to see students take the course’s ideas seriously then generate insights I never would have come up with. Early on one student wrote a paper on the movie Stagecoach which I sent on to Noble. Much more recently, when I inserted into the course Crapanzano’s SERVING THE WORD Literalism in America from the Pulpit to the Bench, a student wrote a stunning analysis of the book deploying Lévi-Strauss’s canonic formula. Shortly after that both her paper and the book came to back to me when one of my Muyuw informants started complaining to me that Europeans believed Muyuw people really thought they came out of the ground, as is stated in their origin myths. The course enabled something I otherwise would not have recognized—a reflection on a mode of thought which if one took literally was either nonsense or infantile… One student, now an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, was told by her Graduate professors at Yale that she was fortunate her undergraduate professors took their work seriously. I’ve recently reread her papers. They remain super. When you ask a lot, people often give a lot.

A SUMMARY: The variants of Everyday Life in America became a kaleidoscopic view of US culture crossing its times—late 18th century to the present, productive, annual and personal cycles; its places—the Texas Panhandle, Southern and Northern churches, ‘Fenway Park,’ Wall Street, Silicon Valley, ‘Fast-Food restaurants,’ ‘banks,’ ‘homes’ and ‘apartments,’ and Masters’ bedrooms and forests; and the theories devised to understand social systems—arguably practices produced by a justified idea that ‘we’ have lost our way –because there is more than one way to live.

ANTHROPOLOGY 334/3340 ECOLOGY & SOCIETY, An Introduction to the New Ecological Anthropology.

Although I taught other undergraduate courses, to be reviewed later, I did not have another one around which I organized as much learning, my own and students’, as A355/3155until I developed this course in the early 1990s. It was first entitled “CULTURE, SPACE AND NATURE, An Introduction to the New Ecological Anthropology. Within several years, however, Virginia Hymes wished to teach a course on the anthropology of time and space and since mine, in both content and title, was so close to her wishes, I adopted the title ECOLOGY & SOCIETY. This course saw me through the end of my professional teaching career and enabled a similar kind of intellectual work I accomplished with the American Culture course. I sought to become competent and in a limited sense good in something I knew very little about. Also initiated with a TA, its enrollment eventually fell below the requirements of that structure. It remained, however, a writing course, though I also used a Midterm and Final Exam format. The exam format required identifying quotes by author and title from the assigned readings and writing short essays about those quotes. The required writing derived from short book synopses students wrote during the first half of the course and a project-paper, quasi-term paper, they wrote during the second half. Over the last years of the course, among those books students could choose to read, summarize and report on every Friday were these: Davis’s LATE VICTORIAN HOLOCAUSTS; Elvin’s THE RETREAT OF THE ELEPHANTS; Flannery’s THE ETERNAL FRONTIER: An Ecological History of North America and Its People (well into the 00’s some people read Flannery’s The Future Eaters); Gammage’s THE BIGGEST ESTATE ON EARTH; Kolbert’s THE SIXTH EXTINCTION; Ruddiman’s PLOWS, PLAGUES AND PETROLEUM; and Shugart’s FOUNDATIONS OF THE EARTH: Global Ecological Change and the Book of Job. The course was labor-intensive on my part, and I enjoyed that.

Circumstances I had the wit to learn from organized the American Culture course, and they did with this one too. First, I was repelled by the developing separation between the Arts and the Sciences building from the 70s on. So, I made the effort to forge a tie to UVa’s Environmental Sciences Department. I did not know it at the time, but its then chair, Hank Shugart, had had a long history of interacting with anthropologists. And although he, like many others in his department, thought their studies needed to be in the “hard sciences,” he knew human beings were responsible for making our current world, and that there needed to be lines of contact among all of us. Shugart’s own expertise was in forest ecology, and forest modeling, so while he welcomed me, I thought I needed ties to geology and geologists. He sent me to a young geologist who had just joined their department and whose primary research was in Africa, along the spreading zones running north/south along the continent’s eastern third. After my summer in Papua New Guinea (PNG) in 1991 she declined to work with me because she understood PNG to be a collision zone, thus having different geological features than those she was interested in (As in all cases like this, there were personal matters at play too.) There ended up being a paradox here. While my research area is the product of the collision between the Austral-India and Pacific plates, the specific region of the Kula Ring is a spreading zone of considerable geological interest (now intensively researched by Geoffrey Abers whom I’ve met and interacted with). Yet that loss was ok since my 1991 discoveries moved me from “ethnogeology” to “ethnobotany.” This pleased Shugart and we’ve been deeply interactive since then.

Assembling a syllabus was an early chore. Somehow, and second, I learned about this new sub-subdiscipline “historical ecology” and of a conference about it Tulane’s Bill Balée was holding in the summer of 1994. Although I was not able to contribute, on my own dime Balée allowed me to sit in on the proceedings. I read Carole Crumley’s recently released HISTORICAL ECOLOGY: Cultural Knowledge and Changing Landscapes on the plane to New Orleans and was taken in by it. Among those attending Balée’s conference were Carole Crumley, Joel Gunn, Neil Whitehead, Darrell Posey, Laura Rival (one of whose essays I was already using), Anna Roosevelt and several others. Overnight I was amidst something new (to me) and the people who were defining it. Before the conference I’d discovered Mark Plotkin’s book for those times, TALES OF A SHAMAN’S APPRENTICE, and had already inserted it in the beginning of my course (where it remained almost to its end). It was like Jane Kramer’s The Last Cowboy: a well-written story, simple and engaging to read but in fact packed with ideas worth exploring.  Significantly, at his conference I learned that Balée and Posey were dubious about Plotkin and his book. By the time I started using Tales, UVa environmental scientists had already mapped the flow of nutrients from (especially north) Africa across the Atlantic to, among other places, the Amazonian rainforests. So early in the book when Plotkin explains how those rainforests were a closed system I could point out in lectures that he was mistaken. Given the time expanse historical ecology opens up, this is significant and throws into relief new questions about the development of domesticated crops across the Americas, as well as the unique and very productive agricultural systems developed in West Africa; a former student’s discussion of the harmattan winds in West Africa adds to this set of intriguing questions. Coupled with, for example, Winterhalder’s critique in HISTORICAL ECOLOLOGY, "Concepts in Historical Ecology: The View from Evolutionary Theory," many aspects of Plotkin’s book became useful for talking about models, the facts required to learn and know something (Plotkin tells a tale Jared Diamond told about Ralph Bulmer worthy of major discussion), and of course the environmental history Plotkin sprinkled through the text.

Significantly, at his conference I learned that Balée and Posey were dubious about Plotkin and his book. By the time I started using Tales, UVa environmental scientists had already mapped the flow of nutrients from (especially north) Africa across the Atlantic to, among other places, the Amazonian rainforests. So early in the book when Plotkin explains how those rainforests were a closed system I could point out in lectures that he was mistaken. Given the time expanse historical ecology opens up, this is significant and throws into relief new questions about the development of domesticated crops across the Americas, as well as the unique and very productive agricultural systems developed in West Africa; a former student’s discussion of the harmattan winds in West Africa adds to this set of intriguing questions. Coupled with, for example, Winterhalder’s critique in HISTORICAL ECOLOLOGY, "Concepts in Historical Ecology: The View from Evolutionary Theory," many aspects of Plotkin’s book became useful for talking about models, the facts required to learn and know something (Plotkin tells a tale Jared Diamond told about Ralph Bulmer worthy of major discussion), and of course the environmental history Plotkin sprinkled through the text.

Third, when I was an undergraduate, I read Edgar Anderson’s PLANTS, MAN& LIFE and knew I wanted a book like that. So, I called Harold Conklin at Yale, told him what I wanted, Anderson’s book for today. He knew exactly what to suggest, Gary Nabhan’s ENDURING SEEDS. Assigned in whole early in the course’s history, as time went along only a few chapters remained useful for my introductory purposes. One of those chapters sketched minor sacrifices Wisconsin Indians made while they were harvesting their “wild rice” in a manner which insured its reproduction for the next year. With this I could introduce Anthropology’s paradigms about sacrificial rites, among other things, and compare those kinds of destructive/productive acts with the beneficial and scientific extraction of guano off the coast of Peru, and the destruction of Chinese human beings that produced, all ‘required’ because by the middle of the 19th century Europeans on North America were exhausting the fertility of their soils. As ethnobotany’s poet, Nabhan opens many lines of inquiry, and my use of him introduced students to others of Nabhan’s writings, giving them new tracks to run down...

From 1994 on Crumley’s HISTORICAL ECOLOGY collection became the course’s moving theoretical center. What I learned from Crumley about the biome/ecotone and hierarchy/heterarchy contrasts, among others, grew in importance as my own researches matured. It was easy to see that the Kula Ring was a complex heterarchical system, as was, I eventually realized, virtually all the Indo-Pacific whose histories and structures Crumley’s work –on scale—helped me fathom (My 2008 “A STRANGER’S VIEW OF BIHAR-RETHINKING RELIGION” flows from this). I discussed my ‘Crumley learning’ with my UVa Environmental Science gurus and at one point was told that they tended to ignore ecotonal phenomena because they made their mathematics too complex. Almost immediately assimilating “ecotone” to “liminal,” and the learning Anthropology had created with that idea since the 1960s, I couldn’t follow the Environmental Science advice, and not only because one of the important trees in the Kula Ring was systematically generated by intentionally created ecotones, it was personified. The tree was, thus, a social fact of immense importance (for anthropology), and a set of facts with which I could integrate complex biological and social relations. For this second research stint an early publication was devoted to the tree and its issues (Damon 1998), material addressed again and turned into the pivotal chapter of my book TREES, KNOTS AND OUTRIGGERS: Environmental Knowledge in the Northeast Kula Ring (Chapter 4, “A Story of Calophyllum, from Ecological to Social Facts”).

It was the mid-1990s when Mark Mosko and I started fiddling with chaos theory for anthropology (resulting in ON THE ORDER OF ‘CHAOS’ Social Anthropology & the Science of ‘Chaos’), and I could fit my reading of Winterhalder’s work into that. So too with Winterhalder’s idea of patches since I eventually realized that the Kula Ring was understood as something like an integrated set of patchy environments. Most of these were “anthropogenic,” a term coming into common currency in the 90s. Sometime in the mid to late 1990s Yale’s Jim Scott appeared to give a serious of lectures. At one of the post-lecture gatherings, we both commented on the fact that now everything seemed to be anthropogenic.

What I discovered in the summer of 1991 transformed my research and eventually this course. I returned to Muyuw hoping to explore an idea which would lead me into ‘ethnogeology,’ an analysis of the islanders’ understanding of the physical form of their island. However, my old Muyuw teachers laughed at my idea. Eventually, however, one of the women who had been like a mother to my wife and me from 1973-75 mentioned something about a tree people used to reproduce their fields’ soil fertility. I knew a lot about Muyuw gardens (and I thought their fields); a central chapter in my 1990 book –“Chapter 5, “Follow the Sun” Order in Muyuw—was devoted to this form and I used it in the early years of this course. Yet I’d never heard anything about this tree before. But precisely because of the garden form’s importance—not unlike Chinese temples, which I saw for the first time in 1991—I immediately deduced that the topic of trees must be exceedingly important. Other people confirmed this woman’s account. And the deduction was correct; when I returned to the island in 1995 to begin the research, I told one of my old teachers –one of the people who had laughed at my 1991 hypothesis—what I was going to do. He just replied “good,” for he knew I knew nothing about something that was vital.

I spent 1991-1995 trying to learn what I needed to know to carry out components of this new research. I visited a lot of herbaria. Then the topics seemed to be “classification” on the one hand and the biochemistry of plants—and soils—on the other. Some of this could be introduced with Plotkin’s book since he dropped the scientific names of flora all over his book while its primary point was the rainforest products, including the people in it, were vital to preserve because of their potential utility—often biochemical—to us. I knew Muyuw people would have their own knowledge about ‘both;’ the question was what I needed to learn to understand them. Thirty years later I think I know some of what I needed to learn. This learning got pulled into my course. When the course started Brent Berlin’s ETHNOBIOLOGICAL CLASSFICATION was still new, and he invited me to Georgia to lecture after my initial 1995 research stint. Soon I coupled a chapter from his book with work by Roy Ellen, the two openly contrasting their perspectives with each other. I wanted students to experience their disagreements over how to understand complicated and well-conceived human action. I learned from both. To this portion of the class, I added my interaction with the systematist who identified the voucher specimens I made of Muyuw flora, Peter Stevens. Known as a radical in the systematics world, Stevens was a serious student of Anthropology—Atran, in addition to Berlin—and proved something that Shugart had said. Shugart told me he couldn’t wait until I met a systematist, a comment I didn’t understand until I got to know Stevens. Occasionally I would repeat things Stevens told me to UVa biologists, and their reactions were on the order of “A systematist would say that!” I came to believe they would say that because they knew more than the botanists. Most of my Muyuw teachers were also pleased that I was interacting with someone who really knew about flora—it was evident I didn’t. Stevens told me they would know much more than he could know about their trees. He got angry when I showed him he was correct about that! In any case, I tried bringing this fantastic world of knowledge into my class, and combined—‘Berlin,’ Ellen and Stevens—they facilitated me moving from classification to modeling in my pursuit of Muyuw forms of knowing and acting.

Many of the scholars Balée assembled for his 1994 conference talked about global warming and relationships between climate and culture. In Crumley and Gunn’s case this derived in part from atmospheric scientist Reid Bryson’s scholarship. Not too long after being exposed to Crumley and Gunn I learned there were two people in UVa’s Environmental Science Department who were also Bryson devotees. One was Patrick Michaels, who was also becoming a bête noire of many in the department (and Scientific establishment) because of his stance against human-generated global warming; he presumed the evident global warming was just another cycle of the kind Bryson featured. I eventually team-taught a course with the other Bryson student, Bruce Hayden. The other team member, Michael Mann, was just then becoming one of the brains in the Global Warming establishment. Mann and Hayden represented different, and very antagonistic, generations of students. I was privileged to interact with both, and Mann remains a casual friend and correspondent. But the climate and culture concern attracted me. While I did not understand much of it, its scope was big, and holistic, yet it demanded precise and detailed knowledge about a great deal to be meaningful. Gunn, in particular, placed himself between the “Arts” and the “Sciences,” working hard to make the latter intelligible and useful to the former.

Within a couple of years of that 1994 gathering I added to my relevant reading Tim Flannery’s first big popular science book, THE FUTURE EATERS, a book that, along with Crumley’s HISTORICAL ECOLOGY, anchored the ‘climate and culture’ segment of the course and facilitated an appreciation of human, climate and environmental relations which I could readily extend from South and East Asia to Australia. It also provided the conceptual tools to fathom a lot that I learned while on Muyuw in 1995 and 1996. A thesis in THE FUTURE EATERS is that Australia is a landscape humans made by fire. My travels in and study of South and East Asia taught me that they are similar anthropogenic landscapes, only made by water. Muyuw is in between this contrast, and my first return in 1998, as the major 1997-98 ENSO was abating, allowed me to understand many things I had before seen or been told but didn’t know enough to understand. All of this was thrilling. Bringing it into a classroom was important but challenging for most students who, of course, couldn’t have had the empirical experience I had so that it could become readily meaningful.

Flannery’s work anticipated by about a decade the work of another UVa Environmental Scientist, Bill Ruddiman and his PLOWS, PLAGUES AND PETROLEUM. Both showed what had seemed impossible, that human action long before the industrial age was sufficient to begin climate change on a large if not global scale. In this time frame I experienced how difficult a subject global warming was becoming, and this was not just a matter of some people ignoring scientific learning. A geologist I interacted with because of sourcing zircons in pots, Bill Dickerson, told me most of the proof about global warming in the Pacific was nonsense. All those islands were sinking, he told me, because North America was still rebounding from the weight that had pushed it down during the last glaciation. When North America was pushed down, Pacific islands went up… Nevertheless, as the culture and climate theme in the course intensified, I was led to begin its first lecture with the Keeling curve from Hawaii’s Manua Loa showing the steady rise in the amount of CO2 in the air. In his essay Winterhalder wrote of the urgency the contemporary situation gave to, in our case, our research and teaching. Then, 1994, I could only observe. Within a decade of the beginning of this course it shared in that urgency.

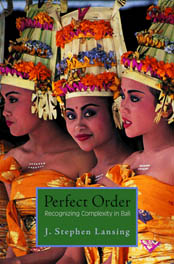

As the first decade of the course was concluding it gained a two-part structure. The first part was effectively conceptual, putting together what I was learning from the natural sciences and the developing ecological studies in Anthropology. The second part was more ethnographic, ostensibly applying the first part’s learning to anthropology’s primary contribution to Western thought, a record of human diversity. For my own interests, and to some extent trying to add what I could to the department’s ethnographic contributions, I devoted this section to the Indo-Pacific, including the landmasses of South and East Asia. Lots of Lansing’s work on Bali was inserted here. From very early in the course’s history I started ending it with a book on Japan by Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, for at least 15 years her Rice As Self. Neither that book nor the subsequent ones I used were ecologically inspired, but they all drew—as does Japan—on Japan’s flora and by that time in the course students could add their own received ecological wisdom. Moreover, most of ecological anthropology’s contributions come from its drawing on other disciplines. And while I used Plotkin’s Tales to get students from social circumstances into environments, I used Ohnuki-Tierney to get them back into social inquiries.

Unintentionally, because I had to stay inside the limits of what I could learn, the first decade of the course’s historical scope remained the last 2500 years of the Holocene. Gunn’s ideas were important here and I used, and saw to it that students learned as a heuristic, periodizations he developed in conjunction with Bryson’s work: e.g. Roman Climatic Optimum (500BC-400Ad); Medieval Climatic Optimum (900AD-1250AD); Little Ice Age (1250-1910). That it was easy to see major human events, including Chinese, Melanesian (and Kula Ring) and Polynesian history, fall roughly into these divisions made them suggestive. Several conjunctions changed this. In no particular order now, these are: 1) Gunn (with whom I’ve been in constant contact since 1994) and his colleagues started focusing on the effects of the relative sea-level stabilization coming some 5-6000 years after the beginning of the Holocene, a periodization that correlates with the Austronesian expansion out of East Asia and, arguably, a change in the scale of human societies; 2) my interaction with Bill Ruddiman, a natural scientist who became puzzled with the apparent anomalous behavior of methane and CO2 during this interglacial period, i.e. the Holocene, and realized human activity had to be the cause. The interaction with Ruddiman was very important. First of all, like other UVa environmental scientists, he saw little empirical reason to support the solar energy variation model Bryson used to construct his periodicities. However, his own researches and publications reproduced some of the variation Bryson’s model attempted to ‘explain.’ In the context of those, and these times, this allowed me to stress the factuality of facts while the interpretations of them could vary; and 3), a focus on Tim Flannery’s  astonishing attempt to provide an ecological