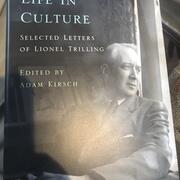

I have been reading the selected letters of Lionel Trilling, entitled Life in Culture: Selected Letters of Lionel Trilling. I like to read collections of letters, because they seem to me and interestingly oblique way into someone’s way of thinking, and they reveal a lot more intimacy more quickly than you would expect. Also, to be honest, letters (and diaries as well) are really great reading just before going to sleep, because they are typically organized and very small parts, and have no large structuring features that might compel or seduce you into reading past the point at which you are tired.

Trilling's letters are a feast of intellectual insight and also a taste of the range of intellectual culture in New York from the 1920s to the 1970s. It has all sorts of fascinating things, including a very interesting revealing letter from Trilling to Max Kadushin, the Jewish Rabbinics scholar who had also taught Trilling Hebrew when the former was a child. (I'll come back to that later.)

There’s lots in here to be interested in: Trilling‘s negotiations with Columbia, as he considered other job offers, in the late 1940s; his surprise, sometimes bordering on a sublimated panic, at the Robert Frost controversy of the early 1960s; and exchange with C. Wright Mills in 1955, which seems to sketch out a contrast between Trilling's view and the so-called "new left" that was emerging.

One exchange seems to me especially poignant in itself and applicable today. At one point in 1967 and 68, Trilling carried on a brief correspondence with one of his old students, a young man named Dotson Rader, who had graduated from Columbia several years before. Rader sounds a bit like one of those revolutionaries that Columbia University had, and maybe we have again these days.

Trilling was warning him to sharpen his intellectual capacities, and he gave him this significant advice:

I think the lesson I would propose is that to jettison awareness of the past is an effectual way of helping to make a cultural revolution, but that if one also undertakes to engage in critical dialectic about the enterprise, a sense of history is a necessary part of the armament.

We don't have Rader's letters to Trilling in this book, and I wish we did. In general, collections of letters without the other side is like watching a tennis match where the camera only focuses on one side of the court; you never actually understand the whole game. Too bad.

But that's a minor complaint, because Trilling's letters are in themselves more than rich enough to carry the book. For me, what’s especially interesting is a letter to Max Kadushin, in 1952, which he wrote on receiving Kadushin's book The Rabbinic Mind. Clearly Trilling was engaged by the book, and it seems to be a great instance of Trilling engaging seriously with religious thought (which he seems otherwise mostly to have evaded--as several of the letters more-or-less admit). Of course this is what became one of the inspirations for his essay “Wordsworth and the Rabbis,“ an essay which I find incredibly powerful and so admirable, as an attempt to engage very seriously in an imagination, or rival imaginations, with which the author feels little instinctual sympathy.

Anyway, a great book of letters. Check it out.